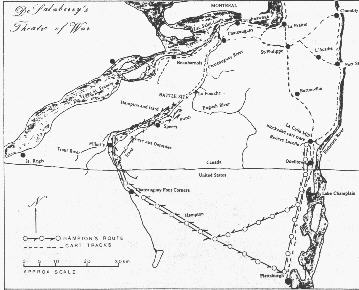

Hampton's first objective was Spears (Ormstown) where a Canadian picket was stationed. Hampton detailed to Izard to lead some light troops in a flanking movement to capture the picket. Izard succeeded, but most of the Canadians eluded him and hurried to inform Charles de Salsberry of the location of Hampton's force. On his part Hampton knew that he was coming close to de Salsberry's lines and he made camp. The Americans marched north in de Salsberry's direction on 22 October. Some ten kilometres separated the two armies, but Hampton's progress was slow. Canadians had cut down trees to impede the Americans, and Hampton had to stop frequently while his men removed the trees and repaired the road.

De Salaberry had been watching Hampton since he crossed the border to Odelltown in September. Informers told him that Hampton would move along the Chateauguay River to meet Wilkinson, and de Salaberry moved his Voltigeurs and select embodied and sedentary militia to the Chateaugay and set up a headquarters at Sainte Martine. He also picked the spot where he would confront Hampton.

At a bend in the river there was a ravine that ran at right angles to the main road, where some cleared land made a satisfactory field of fire. There, on the northern edge of the ravine, he established a line of breastworks on each side of the river, with the stronger line on the west side. The site was also protected by a large swampy wood to the south, where Indians and a few buglers- for extra noise to suggest a large force- would be placed. When the Americans drew near, these breastworks of logs with abatis in front, would be occupied by the light company of the Canadian Fencibles under Captain George Ferguson, two companies of Voltigeurs led by Captains Jean Baptiste and Michel-Louis Jucherau Duchesnay, some Indians under Captain Joseph Lamothe, and a company of Beauharnois militia under Captain Joseph-Marie Longuetin. On the opposite side of the ravine, a small breastwork and abatis would serve as a vantage point to watch for Hampton's vanguard.

At the breastwork on the south(east) side of the river he placed one company of Macdonell's Select Embodied Militia under Captain Charles Daly, a company of chasseurs led by Joseph-Bernard Bruyee, and another company of Select Embodied Militia commanded by Captain de Tonnancour.

About two kilometres downstream was Grant's Ford, and this line on the south bank of the river would intercept American troops attempting a flanking movement to reach the ford and thus cut off de Salaberry's front line from his reserves. As a further measure, de Salaberry had his men build a lunette, a large two sided log fortification.

Some 300-350 men were in these two front lines, one on either side of the river. Behind were reserves numbering 1,400 and commanded by Red George Macdonell. The men had built barricades at intervals of from 200 to 300 metres. Behind the first barricade were Captains Benjamin I'Ecuyer and Dominque Debartzch. Behind these were reserves from the 2nd battalion of embodied militia under Captain Jean Baptiste Hertel de Rouville. Protecting the right flank, in some woods, were sedentary militia from Boucherville and Beauharnois under Lieutenant-Colonel Louis Rene Chaussegros de Lery. Militia under Captain Philippe Panet guarded the foot over the river.

On Monday 25 October, scouts informed Hampton that only 350 Canadians manned de Salaberry's front line on the main road. Hampton chose Colonel Robert Purdy to lead a flanking operation to march on Grant's ford from the south shore, with a force of 1,500 from the 4th, 32nd and 34th regiments of American infantry. Once Purdy had reached the ford and was ready to cut off de Salaberry's front line from his reserves, he was to attack and when Hampton heard the shooting he would order Brigadier Izard to lead a frontal assault. The guides assigned to lead Purdy's force complained that they did not know the way, but Hampton saw no alternative and trusted to luck. Purdy left on the night of the 25th, but his men did not make good time. The guides led them, deliberately or not, through a hemlock swamp. In fact, they never did reach the ford; when they found the river bank they were far short of the ford, and in front of de Salaberry's line on the south side of the river.

On the morning of the 26th, Hampton began his advance towards de Salaberry's line on the north shore of the river, but he stopped and waited out of range for the shots of Purdy's men that would tell him that the subordinate was in position. When Hampton did hear firing, Purdy was not at the ford, but exchanging shots with Captain Bruyere's chasseurs armed with rifles. The time was perhaps 2:00 p.m. when Hampton went into action.

Some versions suggest that de Salaberry started the battle and fired the first shot. When an American officer who knew some french called on the Canadians to surrender, de Salaberry shot him, and the cheer that rose from the front lines resounded as the reserves to it up. Bugles sounding from the woods to the south, and from all the lines added to the din. The shooting continued for hours, the front line on the main road holding it's own, while the front line on the south was contending with Purdy's confused force. Some time after 4:00 p.m. Hampton realized that Purdy was being battered and had no hope of reaching the ford to outflank de Salaberry, and disheartened he ordered a withdrawl. De Salaberry had stood on a stump throughout the battle, and he later wrote to his father that at the battle he rode a wooden horse.

North of the battle ground, Sir George Prevost, and Major-General Louis de Watteville were nearly at the line, with escorts but no reinforcements. Fortunately, de Salaberry would not need help, although he did not know that at the time. He fully expected Hampton to regroup and try again, and he kept his barricades manned and sent a force to pursue the Americans. However, Hampton had had enough.

Purdy led the rearguard, taking up a position beyond the bend in the road. Gradually he fell back, andpursuing troops found abandoned equipment strewn along the road. Indians following and lurking in the woods further unnerved the soldiers shivering in their inadequate clothing.

De Salaberry's casualties were light. Four Select Embodied Militia were killed and four wounded, and three Voltigeurs had been wounded. Hampton estimated that fifty of his men had been killed, but his losses could have been higher. The Canadians buried forty American dead and the Americans buried some of their own. Thus ended the battle that may well have saved Montreal in October 1813.

**Please Note** "Abitis" are branches and sticks that have been shapened to a point and are mixed and jammed together in front of a defensive position. This when confronted is very difficult to get through.